|

§ 4

|

RESEARCH IN PHILOSOPHY

|

|

Boring:

Interesting: Boring: Interesting: Boring: Interesting: Boring: Interesting: |

"Hobbes and Spinoza on Human Rights"

"Alternative Perspectives on Human Rights: Hobbes and Spinoza on Rights as Power" "Kierkegaard’s Use of Socrates in his Pseudonymous Works" "Kierkegaard’s Socrates: Leaping Past the Reasonable" "Cicero’s Adoption of Stoicism" "A Tale of Two Ciceros: Searching for the Stoic Cicero" "Augustine on Moral Order" "Singing a Song of Degrees: Augustine on the Harmony of Moral Order." |

4.3 Creating a Working Outline

Once you have your thesis statement written and you have complied a preliminary collection of notes, you probably will want to create a very general working outline to help determine the direction of your paper. Your working outline need not be more than a few lines, and should indicate the major subdivisions of your paper.

Let’s pretend for a moment that the topic of your paper is on Kierkegaard’s use of the figure of Socrates in his philosophical writings. Your working title is "Kierkegaard’s Socrates: Leaping Past the Reasonable." Your thesis for this paper might be something like the following: "In such pseudonymous works as The Sickness unto Death and The Philosophical Fragments Kierkegaard uses Socrates to represent a rationally based mode of religiousness. In attacking Socrates he is actually attempting to substitute this philosophical model of religiousness with a more paradoxically grounded—and hence more distinctively Christian—model."

Your working outline for such a paper might look something like this:

Let’s pretend for a moment that the topic of your paper is on Kierkegaard’s use of the figure of Socrates in his philosophical writings. Your working title is "Kierkegaard’s Socrates: Leaping Past the Reasonable." Your thesis for this paper might be something like the following: "In such pseudonymous works as The Sickness unto Death and The Philosophical Fragments Kierkegaard uses Socrates to represent a rationally based mode of religiousness. In attacking Socrates he is actually attempting to substitute this philosophical model of religiousness with a more paradoxically grounded—and hence more distinctively Christian—model."

Your working outline for such a paper might look something like this:

Kierkegaard's Socrates: Leaping Past the Reasonable

I. Introduction: Kierkegaard’s

Ambiguous Use of Socrates in the Pseudonymous Works

II. The Distinction Between Religiousness A (Philosophical Wisdom) and Religiousness B (Christian Faith) in the Concluding Unscientific Postscript

III. Socratic Recollection vs. Christian Faith in the Philosophical Fragments

IV. Sin-as-Ignorance vs. Sin-as-Defiance in the Sickness Unto Death

V. Conclusion: Evaluating Kierkegaard’s Use of Socrates

II. The Distinction Between Religiousness A (Philosophical Wisdom) and Religiousness B (Christian Faith) in the Concluding Unscientific Postscript

III. Socratic Recollection vs. Christian Faith in the Philosophical Fragments

IV. Sin-as-Ignorance vs. Sin-as-Defiance in the Sickness Unto Death

V. Conclusion: Evaluating Kierkegaard’s Use of Socrates

Consider your working outline a preliminary vision of your paper. As you continue reading on your topic, you may find it necessary to revise this outline to fit your new ideas on the subject. This is perfectly acceptable. Your working outline is a guide, and when any guide no longer is able to effectively lead you towards your goal (the clear defense of your thesis), it should be substituted for another guide that can.

Your working outline should be brief enough to provide some overall direction to your research. As you continue to read and develop a more nuanced understanding of your subject, you'll probably find it helpful to expand this working outline into a more detailed final outline. A final outline would typically include every major point that you will be making in your paper.

Your working outline should be brief enough to provide some overall direction to your research. As you continue to read and develop a more nuanced understanding of your subject, you'll probably find it helpful to expand this working outline into a more detailed final outline. A final outline would typically include every major point that you will be making in your paper.

4.4 Preparing Your Introduction

As you write your introductory paragraph(s), remember that your introduction is yet another vehicle to entice the reader to delve into your paper. It might be helpful for you to remember that the Latin term for introduction is "exordium" which literally means "beginning a web." Your introduction should captivate the reader so that he is caught in the web of your writing. Try to find an interesting way to state your thesis to the reader so that he will both understand your project in writing the paper and will want to read further.

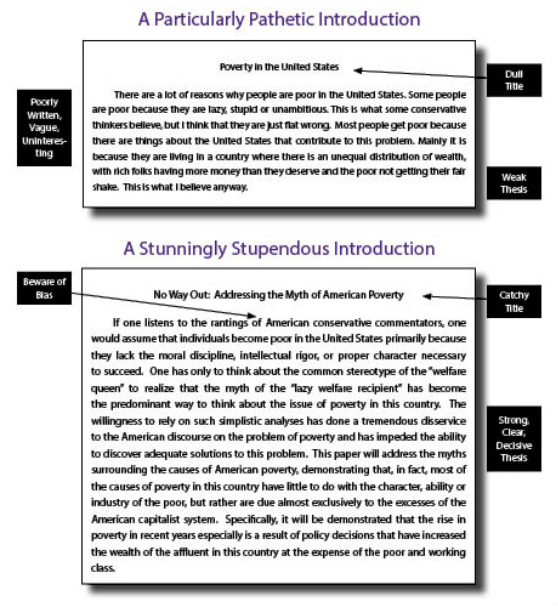

Here is an example of a weak and a strong introduction:

Here is an example of a weak and a strong introduction:

4.5 A Few Picky Matters

You are now at the stage in your research where you can actually start thinking about writing the body of your paper. Before you begin writing, however, there are a few points about the format of your paper that you should keep in mind:

As you begin to write, you should also keep the following few rules in mind and try to observe them consistently throughout your entire paper:

- The paper upon which you will be printing should be white, 8 ½ - 11" paper of good quality.

- The type that you use when printing any college paper should always be 12 point, Times New Roman.

- Papers should also always be double-spaced throughout.

- Margins on all college papers should be 1".

- Paragraphs should be indented ½". Do not skip lines between paragraphs!

- Block quotes should be double spaced and indented 1 inch from the left margin of your paper [In Word: Highlight the text that you would like to double indent and move the buttons on the ruler bar ½ inch on the left. If your ruler bar isn’t visible on the top of your screen, go to View > Ruler Bar].

- All college papers should be stapled in the top, left hand corner of the page (paper clips should be avoided since they can fall off). Do not put your paper in a binder or folder unless specifically told to by your instructor!

As you begin to write, you should also keep the following few rules in mind and try to observe them consistently throughout your entire paper:

- Foreign words and terms not used frequently in English should be put in italics.

- The first time you use a person’s name in your text, write it out fully [e.g., Immanuel Kant]. After that you need only to give the person’s last name (e.g., Kant)—unless, of course, you are referring to two or more persons with the same last name.

- Numbers from one to nine should be spelled out; for numbers 10 and above, use arabic numerals.

- Punctuation. One space should be used after a period (.), a colon (:), a comma (,), or a semi-colon (;).

No spacing should be used before or after a dash (—). [By the way, don’t be afraid to try to incorporate forms of punctuation like colons, dashes and semi-colons into your paper. It may take a bit of practice to learn how to use such "exotic" forms of punctuation like these, but your writing will benefit tremendously by using them on occasion in a paper. Check the on-line version of Elements

of Style for more information on proper use of punctuation in writing]. - Titles of books and journals should be put in italics; titles of articles should be placed in "quotation marks."

- The following abbreviations may be used only within parenthetical comments: cf. = compare; e.g. = for example; etc. = and so forth; i.e = that is; viz = namely; vs. = versus. APA advises paper writers to avoid abbreviations when possible.

- Avoid gender bias when writing your paper (e.g., use "police officer" rather than "policeman" and "he or she" rather than "he" when the specific gender of the person in question is not relevant).

- When writing your paper avoid using slang (e.g., "a really cool illustration") and contractions (instead of "it’s" use "it is").

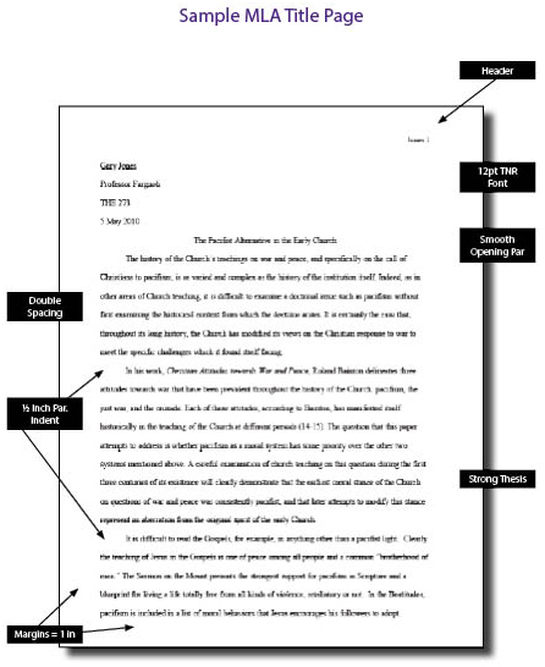

4.6 Sample MLA Title and Text Pages

Cover pages are not used in MLA format. Instead, first page headings are used and include (1) your name, (2) your instructor's name, (3) the course name, and (4) the date in the left hand margin, as shown in the example below:

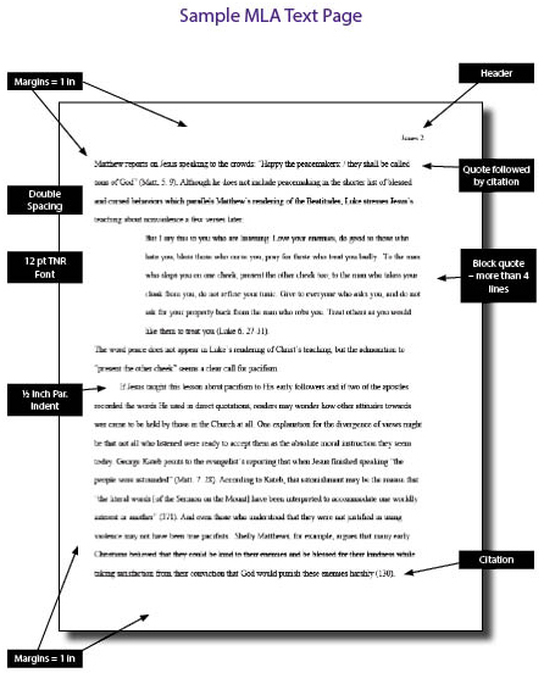

Subsequent pages should include a header in the top right hand corner that includes your last name followed by the page number (Jones 2), as shown in the following example:

© Michael S. Russo, 2002. Updated 2011. All of the content on this webpage is copyright. The materials on this webpage may not be modified, posted or transmitted without the prior consent of the author. Permission is granted to print out copies for educational purposes and for personal use only. No permission is granted for commercial use.