THE HELLENISTIC AGE: FROM ALEXANDER TO AUGUSTUS

Michael S. Russo

Molloy College

I. Beginning of the Hellenistic Age

The Hellenistic age is the period between the death of Alexander the Great and the rise of the Roman Empire under Augustus--that is, from 323 B.C. to 30 B.C. During these three hundred years, Greek culture dominated much of the eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East. The term Hellenistic is also used to distinguish this period from the Classical (or Hellenic) period, which preceded it.

We have already seen that the Peloponnesian War, which lasted from 431-404 B.C., left Greek city states such as Athens and Sparta vulnerable to attack. When this attack occurred, it came from an unlikely source--a seemingly backwards city state in the wilds of Northern Greece called Macedonia. The king of that city, Philip, introduced many military improvements to his infantry and cavalry that enabled Macedonia to conquer rivals such as Thessaly and Thrace. Finally, in 338 B.C. Philip conquered an allied Greek army led by Athens at the Battle of Chaeronea, marking the end of the independent Greek city-state.

Having conquered Greece, Philip was preparing for an invasion of Asia Minor as well when he was assassinated. He was succeeded by his twenty year old son, Alexander [the Great], who took up where his ambitious father had left off. Alexander may have been Macedonian by birth but he was thoroughly Hellenized by education. In fact, his teacher was none other than the philosopher Aristotle, another famous Macedonian.

Alexander had such an admiration for things Greek that his ambition was to Hellenize the world. With an army of about 30,000 soldiers he proceeded to defeat the Persian army led by the Emperor Darius III at the Battle of Issus in 333 B.C. and went on to conquer Syria and Palestine as well. From Syria Alexander proceeded to Egypt, where he humbly had himself declared the son of the sun god, Ra. Spending the winter with his army in Egypt, he founded a city which was to become a center for Greek culture and learning in Egypt and gave his name to it -- Alexandria.

During the Spring of 331, Alexander retuned to Syria to decisively defeat the Persian army, which had risen up to oppose him. After this, he proceeded on to India with dreams of ruling that wealthy country. He only succeeded in conquering the northwestern part of India, however, before his soldiers began to complain about the intolerable climate of that region and he was forced to return to Persia again.

The Hellenistic age is the period between the death of Alexander the Great and the rise of the Roman Empire under Augustus--that is, from 323 B.C. to 30 B.C. During these three hundred years, Greek culture dominated much of the eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East. The term Hellenistic is also used to distinguish this period from the Classical (or Hellenic) period, which preceded it.

We have already seen that the Peloponnesian War, which lasted from 431-404 B.C., left Greek city states such as Athens and Sparta vulnerable to attack. When this attack occurred, it came from an unlikely source--a seemingly backwards city state in the wilds of Northern Greece called Macedonia. The king of that city, Philip, introduced many military improvements to his infantry and cavalry that enabled Macedonia to conquer rivals such as Thessaly and Thrace. Finally, in 338 B.C. Philip conquered an allied Greek army led by Athens at the Battle of Chaeronea, marking the end of the independent Greek city-state.

Having conquered Greece, Philip was preparing for an invasion of Asia Minor as well when he was assassinated. He was succeeded by his twenty year old son, Alexander [the Great], who took up where his ambitious father had left off. Alexander may have been Macedonian by birth but he was thoroughly Hellenized by education. In fact, his teacher was none other than the philosopher Aristotle, another famous Macedonian.

Alexander had such an admiration for things Greek that his ambition was to Hellenize the world. With an army of about 30,000 soldiers he proceeded to defeat the Persian army led by the Emperor Darius III at the Battle of Issus in 333 B.C. and went on to conquer Syria and Palestine as well. From Syria Alexander proceeded to Egypt, where he humbly had himself declared the son of the sun god, Ra. Spending the winter with his army in Egypt, he founded a city which was to become a center for Greek culture and learning in Egypt and gave his name to it -- Alexandria.

During the Spring of 331, Alexander retuned to Syria to decisively defeat the Persian army, which had risen up to oppose him. After this, he proceeded on to India with dreams of ruling that wealthy country. He only succeeded in conquering the northwestern part of India, however, before his soldiers began to complain about the intolerable climate of that region and he was forced to return to Persia again.

|

After conquering most of the civilized world, Alexander suddenly died in 323 B.C. at the age of 33. Because he had made no preparation for a successor, his empire was split into three different parts by his generals, who each founded dynasties of their own. Thus Egypt came to be ruled by the Ptolemies, Macedonia and Greece by the Antigonids, and Syria and Persia by the Seleucids.

Because the kings in each of these regions believed that they alone were the legitimate heirs of Alexander, war between the kingdoms was a perpetual feature of the Hellenistic age. On the positive side, however, Alexander's vision of a Hellenized world was largely realized by him and his successors. In cities as far apart as Alexandria in Egypt, Pergamum in Asia Minor and Antioch in Syria, Greek art, literature and philosophy flourished. |

II. The Achievements of the Hellenistic Age

Because they had defeated the wealthy Persian empire, Alexander and his successors had ample amounts of wealth to spend lavishly on building projects and the arts. The Ptolemies, for example, built a huge library in Alexandria with the modest aim of gathering all the known books in the world. Attached to the library was a museum (the term which is still used today literally means "place of the muses"), where scholars would produce encyclopedias of knowledge.

Tremendous achievements during this period were also made in the areas of science and art: Aristarchus of Samos put forth the theory that the earth revolves around the sun and rotates daily on its own axis; in Alexandria, Euclid summed up all the geometric knowledge of his age in the form of a textbook (a work that is still referred to to this day); Archimedes of Syracuse worked out many important theorems in mathematics.

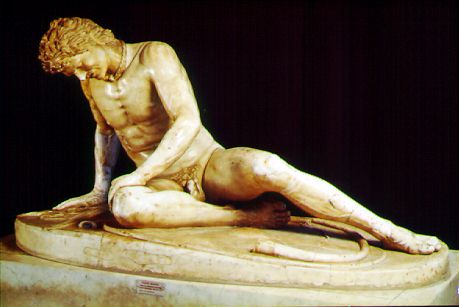

In the arts, sculpture became more realistic. Whereas sculptors during the classical period aimed at portraying an idealized version of human beings---typically with features portraying little emotion -- Hellenistic sculptors aimed at more naturalistic depictions. Female nudes and busts of ordinary, less than perfect people also become quite common during this period.

Because they had defeated the wealthy Persian empire, Alexander and his successors had ample amounts of wealth to spend lavishly on building projects and the arts. The Ptolemies, for example, built a huge library in Alexandria with the modest aim of gathering all the known books in the world. Attached to the library was a museum (the term which is still used today literally means "place of the muses"), where scholars would produce encyclopedias of knowledge.

Tremendous achievements during this period were also made in the areas of science and art: Aristarchus of Samos put forth the theory that the earth revolves around the sun and rotates daily on its own axis; in Alexandria, Euclid summed up all the geometric knowledge of his age in the form of a textbook (a work that is still referred to to this day); Archimedes of Syracuse worked out many important theorems in mathematics.

In the arts, sculpture became more realistic. Whereas sculptors during the classical period aimed at portraying an idealized version of human beings---typically with features portraying little emotion -- Hellenistic sculptors aimed at more naturalistic depictions. Female nudes and busts of ordinary, less than perfect people also become quite common during this period.

During this period, philosophy became accessible to a much wider audience than it had previously been. Many affluent members of the population, including women, began to study philosophy and to attend lectures of popular philosophers.

The major preoccupation of philosophy during this period was focused on the problem of human happiness. This focus makes sense when one considers the turbulent times in which many men and women were living. Long-autonomous city states had been swallowed by larger kingdoms in which power was held by distant --- and at times perhaps capricious -- monarchs. No longer were people able to view participation in the life of the polis as a means of ensuring happiness. Instead they were forced to look within themselves for a tranquility (ataraxia) that more often than not was lacking in the larger world, where blind chance seemed to govern human affairs.

Into this unsettling environment, several new schools of philosophy arose: the Stoics, who believed that a life of virtue offered human beings the best chance for happiness; the Epicureans, who pursued simple pleasures that could not be taken away by chance; the Skeptics, who, by doubting everything, believed that they could attain a state of perfect tranquility; and finally the Cynics, who preached a return to nature and a rejection of conventional mores as the key to man's felicity.

The major preoccupation of philosophy during this period was focused on the problem of human happiness. This focus makes sense when one considers the turbulent times in which many men and women were living. Long-autonomous city states had been swallowed by larger kingdoms in which power was held by distant --- and at times perhaps capricious -- monarchs. No longer were people able to view participation in the life of the polis as a means of ensuring happiness. Instead they were forced to look within themselves for a tranquility (ataraxia) that more often than not was lacking in the larger world, where blind chance seemed to govern human affairs.

Into this unsettling environment, several new schools of philosophy arose: the Stoics, who believed that a life of virtue offered human beings the best chance for happiness; the Epicureans, who pursued simple pleasures that could not be taken away by chance; the Skeptics, who, by doubting everything, believed that they could attain a state of perfect tranquility; and finally the Cynics, who preached a return to nature and a rejection of conventional mores as the key to man's felicity.

III. The Rise of Rome

While Alexander was carving out his empire in the east, the people of Rome began to carve out their own empire in Italy and North Africa. The three Punic Wars with Carthage (264-241, 218-202, 149-146 BC) marked the decline of that city as a major power in the Mediterranean and the beginning of Rome's dominance over the region. Over the next two centuries Rome would go on to gain control over most of Western Europe and to conquer much of Alexander's former empire in the east.

While Rome was at war with Carthage in the West, Hellenistic civilization was alive and well in the three kingdoms carved out by Alexander's successors. But the constant rivalry among these kingdoms left them vulnerable to conquest by Rome: In 197 a Roman army defeated the forces of Philip V of Macedonia, and in 190 they defeated the army of Antiochus, King of Syria at Magnesia, giving Rome dominance over these regions. The conquest of these Hellenized lands led to the gradual assimilation of Greek culture (philosophy, literature, art, religion) into Roman society.

In the West, Rome continued to expand rapidly. The First Punic War had given Sicily, Sardinia and Corsica to Rome, the Second resulted in the annexation of most of Spain, and the Third to the annexation of Carthage itself. During the Gallic Wars of 58-51 BC, Julius Caesar conquered much of present day Germany and France. His success led to the creation of the First Triumvirate in 59 B.C. dividing the rule of Rome and its provinces among three individuals--Caesar, Pompey and Crassus. With the death of Crassus in Persia, a growing rivalry between Caesar and Pompey became inevitable. When the Senate, with Pompey's support, ordered Caesar to surrender his provinces in Rome and to disband his army, Caesar realized that he would have to fight against Rome itself to preserve his power. On January 7th, 49 B.C., he crossed the Rubicon, plunging the Republic into civil war and effectively marking the death of the Republic.

Pompey was eventually murdered in Egypt and Caesar became supreme ruler over Rome from 48-44 B.C. His assassination on the Ides of March in 44 B.C. again plunged Rome into civil war. A Second Triumvirate established a three man dictatorship, consisting of Mark Anthony, one of Caesar's generals, Octavian, Caesar's nephew, and Lepidus, a nobody who would quickly disappear from the political scene. Once again conflict occurred with Anthony establishing himself in Egypt and in the bed of Cleopatra, the Queen of that country. At the naval battle of Actium in 31 B.C. Anthony's forces were destroyed and both he and Cleopatra were forced to commit suicide.

IV. The Pax Romana

The defeat of Anthony at Actium left Octavian the undisputed master of one of the largest empires that the world had ever known. Taking the name Augustus Caesar, he became, in effect, Emperor over this vast domain. Unlike his unfortunate uncle Julius, however, Augustus masked his ambitions by allowing republican institutions to remain in place during his 43 year rule (29 B.C. - 14 A.D.).

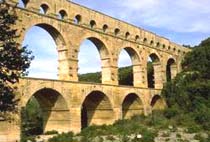

Augustus' greatest achievement was that he managed to finally bring some peace to Rome and its provinces. After almost twenty years of civil wars, the people of Rome welcomed the prosperity and high culture that this peace fostered. With Roman rule firmly established, the Mediterranean became virtually a Roman lake, which thousands of trading ships would cross with their merchandise. Augustus boasted before his death that he found Rome a city of bricks and left it a city of marble, referring to the numerous temples and public buildings that were raised up during his reign.

While Alexander was carving out his empire in the east, the people of Rome began to carve out their own empire in Italy and North Africa. The three Punic Wars with Carthage (264-241, 218-202, 149-146 BC) marked the decline of that city as a major power in the Mediterranean and the beginning of Rome's dominance over the region. Over the next two centuries Rome would go on to gain control over most of Western Europe and to conquer much of Alexander's former empire in the east.

While Rome was at war with Carthage in the West, Hellenistic civilization was alive and well in the three kingdoms carved out by Alexander's successors. But the constant rivalry among these kingdoms left them vulnerable to conquest by Rome: In 197 a Roman army defeated the forces of Philip V of Macedonia, and in 190 they defeated the army of Antiochus, King of Syria at Magnesia, giving Rome dominance over these regions. The conquest of these Hellenized lands led to the gradual assimilation of Greek culture (philosophy, literature, art, religion) into Roman society.

In the West, Rome continued to expand rapidly. The First Punic War had given Sicily, Sardinia and Corsica to Rome, the Second resulted in the annexation of most of Spain, and the Third to the annexation of Carthage itself. During the Gallic Wars of 58-51 BC, Julius Caesar conquered much of present day Germany and France. His success led to the creation of the First Triumvirate in 59 B.C. dividing the rule of Rome and its provinces among three individuals--Caesar, Pompey and Crassus. With the death of Crassus in Persia, a growing rivalry between Caesar and Pompey became inevitable. When the Senate, with Pompey's support, ordered Caesar to surrender his provinces in Rome and to disband his army, Caesar realized that he would have to fight against Rome itself to preserve his power. On January 7th, 49 B.C., he crossed the Rubicon, plunging the Republic into civil war and effectively marking the death of the Republic.

Pompey was eventually murdered in Egypt and Caesar became supreme ruler over Rome from 48-44 B.C. His assassination on the Ides of March in 44 B.C. again plunged Rome into civil war. A Second Triumvirate established a three man dictatorship, consisting of Mark Anthony, one of Caesar's generals, Octavian, Caesar's nephew, and Lepidus, a nobody who would quickly disappear from the political scene. Once again conflict occurred with Anthony establishing himself in Egypt and in the bed of Cleopatra, the Queen of that country. At the naval battle of Actium in 31 B.C. Anthony's forces were destroyed and both he and Cleopatra were forced to commit suicide.

IV. The Pax Romana

The defeat of Anthony at Actium left Octavian the undisputed master of one of the largest empires that the world had ever known. Taking the name Augustus Caesar, he became, in effect, Emperor over this vast domain. Unlike his unfortunate uncle Julius, however, Augustus masked his ambitions by allowing republican institutions to remain in place during his 43 year rule (29 B.C. - 14 A.D.).

Augustus' greatest achievement was that he managed to finally bring some peace to Rome and its provinces. After almost twenty years of civil wars, the people of Rome welcomed the prosperity and high culture that this peace fostered. With Roman rule firmly established, the Mediterranean became virtually a Roman lake, which thousands of trading ships would cross with their merchandise. Augustus boasted before his death that he found Rome a city of bricks and left it a city of marble, referring to the numerous temples and public buildings that were raised up during his reign.

The reign of Augustus was also a golden age for literature. It was during this period that Virgil wrote his masterpiece the Aeneid, Ovid composed his Odes and Livy, his history of Rome. In the area of philosophy, the Romans were significantly less innovative, being content to ride on the backs of their illustrious Greek predecessors. Cicero, for example, was content to do little more than summarize Greek thought in his major philosophical works, The Tusculan Disputations and On the Ends of Good and Evil (De Finibus). On the other hand, Lucretius' On the Nature of Things and Seneca's Moral Epistle's and Essays represent innovative developments within Epicurean and Stoic thought respectively.

|

It should also not be forgotten that it was during Augustus' reign that Jesus was born in Bethlehem. The peace that was forged by Augustus and his immediate predecessors allowed the religion to spread in a way that it could not have in less unified times. In fact, within the span of four centuries, Christianity would become the dominant religion of the Empire -- an amazing accomplishment, given the religion's humble origins as a marginalized Judean sect and the persecution that it would be forced to endure while it was spreading.

But that is another story completely. |

V. Suggestions for Further Reading

- Burby, J.B. and Barber, E.A. The Hellenistic Age: Aspects of Hellenistic Civilization. New York: W.W. Norton, 1970.

- Crow, Charles. Greece: The Magic Spring. New York: Harper and Row, 1970.

- Freeman, Charles. Egypt, Greece and Rome: Civilizations of the Ancient Mediterranean. New York: Oxford, 1996.

- ---. The Greek Achievement. New York: Viking, 1999.

- Grant, Michael. The Founders of the Western World: A History of Greece and Rome. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1991.

- Green, Peter. Alexander to Actium: The Historical Evolution of the Hellenistic Age. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990.

- Hardy, W.G. The Greek and Roman World. Cambridge, MA: Schenkman, 1962.

- Walbank, F.W. The Hellenistic World. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1992.

© Michael S. Russo, 2001. This text is copyright. Permission is granted to print out copies for educational

purposes and for personal use only. No permission is granted for commercial use.