THE FABULOUS FIFTH CENTURY: ATHENS IN THE AGE OF PERICLES

Michael S. Russo

Molloy College

I. From Crisis to Triumph: The Persian Wars (499-480 BC)

The beginning of the Fifth Century BC in Greece was marked by the Persian Wars which started in 499 and continued on and off until 480. Persia at this time had an empire which spread across half of known Asia (the area that was under its control was actually even larger than that of Rome at its peak). It also had a huge multi-national army that it used to conquer neighboring states.

The beginning of the Fifth Century BC in Greece was marked by the Persian Wars which started in 499 and continued on and off until 480. Persia at this time had an empire which spread across half of known Asia (the area that was under its control was actually even larger than that of Rome at its peak). It also had a huge multi-national army that it used to conquer neighboring states.

Although for some time Greek colonies bordering the Persian empire had been paying tributes to Persia, in 499 they began to rebel. The city of Athens agreed to assist those cities that were fighting the Persians, going so far as to destroy Sardis, an important Persian city. Once rebellion had been quelled in the colonies, the ruler of Persia, Darius the Great, decided to turn his attention to those Greek cities on the mainland that had defied him. In 490, he landed a large force at Marathon, a bay only 26 miles from Athens. Despite being confronted by the much larger Persian army, Athens eventually won the battle, killing 6,400 Persians and losing only 192 of its own soldiers. Darius died in 486 and he was succeeded by his son Xerxes. Gathering together an even larger force than his father had (approximately 300,000 soldiers and 600 ships), Xerxes decided to pick up where his father had left off and invaded Greece in 480.

Herodotus, the great historian of the Perisan Wars, makes it clear in his Histories that Xerxes was looking to revenge himself primarily against Athens for the humiliating defeat that city had inflicted upon his father:

"I will bridge the Hellespont and march an army through Europe into Greece, and punish the Athenians for the outrage they committed upon my father and upon us. As you saw, Darius himself was making his preparations for war against these men; but death prevented him from carrying out his purpose. I therefore, on his behalf, and for the benefit of all my subjects, will not rest until I have taken Athens and burnt it to the ground, in revenge for the injury which the Athenians without provocation once did to me and my father....If we crush the Athenians and their neighbors in the Peloponnese, we shall extend the empire of Persia so that its boundaries will be God's own sky, so that the sun will not look down upon any land beyond the boundaries of what is ours" (Histories 7.8).

On the way to Athens, however, the Persian army was bottled up at the pass of Thermopylae by the Spartans under the leadership of King Leonidas. Although the Spartans were able to hold the Persians off for some time, eventually Leonidas and all his men were killed in battle. Xerxes proceeded to Athens, only to discover the city deserted and the Greek army and navy removed to Salamis. In retaliation, he had the city of Athens burnt to the ground and the Acropolis destroyed. The Greeks eventually scored another major victory against the Persians at Salamis, where under the leadership of Themistocles they decisively defeated the Persian navy in battle on September 23, 480.

II. Greek Society After the Persian Wars

As a result of their victory over the Persians at Salamis, Greek society would have the opportunity to blossom during the next century. Under the continued leadership of Themistocles, the Athenians rebuilt their city and erected new temples on top of the Acropolis.

It should be noted that at this time Greece was not one unified country, but was made up of a number of independent city-states, including Athens, Sparta, Corinth and Thebes. Although there would always be some degree of conflict and tension among the different Greek city-states, after the Persian Wars, the Greeks were blessed by a period of relative peace and tranquility that would last for the next 50 years until the start of the Peloponnesian War in 399.

Athens, the real winner of the Persian Wars, became the most dominant of the Greek city-states. In order to secure the protection of Greece against future foreign invaders, the Athenians established the Delian League. Each of the members of this league agreed to contribute either ships or funds for their mutual defense. In a sign of things to come, Sparta chose not to participate in the league.

This network of neighboring city-states led to an expansion of commerce and an increase in prosperity throughout Greece. The combination of peace and prosperity benefited Athens in particular, enabling the city to strengthen itself militarily and to begin an extensive public building program.

Herodotus, the great historian of the Perisan Wars, makes it clear in his Histories that Xerxes was looking to revenge himself primarily against Athens for the humiliating defeat that city had inflicted upon his father:

"I will bridge the Hellespont and march an army through Europe into Greece, and punish the Athenians for the outrage they committed upon my father and upon us. As you saw, Darius himself was making his preparations for war against these men; but death prevented him from carrying out his purpose. I therefore, on his behalf, and for the benefit of all my subjects, will not rest until I have taken Athens and burnt it to the ground, in revenge for the injury which the Athenians without provocation once did to me and my father....If we crush the Athenians and their neighbors in the Peloponnese, we shall extend the empire of Persia so that its boundaries will be God's own sky, so that the sun will not look down upon any land beyond the boundaries of what is ours" (Histories 7.8).

On the way to Athens, however, the Persian army was bottled up at the pass of Thermopylae by the Spartans under the leadership of King Leonidas. Although the Spartans were able to hold the Persians off for some time, eventually Leonidas and all his men were killed in battle. Xerxes proceeded to Athens, only to discover the city deserted and the Greek army and navy removed to Salamis. In retaliation, he had the city of Athens burnt to the ground and the Acropolis destroyed. The Greeks eventually scored another major victory against the Persians at Salamis, where under the leadership of Themistocles they decisively defeated the Persian navy in battle on September 23, 480.

II. Greek Society After the Persian Wars

As a result of their victory over the Persians at Salamis, Greek society would have the opportunity to blossom during the next century. Under the continued leadership of Themistocles, the Athenians rebuilt their city and erected new temples on top of the Acropolis.

It should be noted that at this time Greece was not one unified country, but was made up of a number of independent city-states, including Athens, Sparta, Corinth and Thebes. Although there would always be some degree of conflict and tension among the different Greek city-states, after the Persian Wars, the Greeks were blessed by a period of relative peace and tranquility that would last for the next 50 years until the start of the Peloponnesian War in 399.

Athens, the real winner of the Persian Wars, became the most dominant of the Greek city-states. In order to secure the protection of Greece against future foreign invaders, the Athenians established the Delian League. Each of the members of this league agreed to contribute either ships or funds for their mutual defense. In a sign of things to come, Sparta chose not to participate in the league.

This network of neighboring city-states led to an expansion of commerce and an increase in prosperity throughout Greece. The combination of peace and prosperity benefited Athens in particular, enabling the city to strengthen itself militarily and to begin an extensive public building program.

III. The Age of Pericles (461-429)

Pericles was born in 495 BC to one of the foremost families in Athens. After the defeat of Persia by Athens during the Persian Wars, Pericles rose to power in Athens and worked tirelessly to strengthen the city against future aggression. During the fifth century the highest position in Athenian government was held by ten Strategi, or generals, who commanded the army and navy and who were in charge of foreign affairs. Pericles was re-elected to this body continuously from 461until his death in 429.

Pericles was born in 495 BC to one of the foremost families in Athens. After the defeat of Persia by Athens during the Persian Wars, Pericles rose to power in Athens and worked tirelessly to strengthen the city against future aggression. During the fifth century the highest position in Athenian government was held by ten Strategi, or generals, who commanded the army and navy and who were in charge of foreign affairs. Pericles was re-elected to this body continuously from 461until his death in 429.

According to Thucydides, Pericles' power came not only from his authority as a general, but because of the influence he had over the Athenian assembly. He has been described as an incorruptible politician, a master speaker and a lucid thinker, though some of his contemporaries described his manner as somewhat haughty. His popularity in the assembly was undoubtedly derived from his extraordinary abilities as a democratic leader, for "being...a man of transparent integrity, he was able to control the multitude in a free spirit; he led them rather than was led by them." (Thucydides, History)

Pericles so dominated Athenian politics that the period in which he ruled has come to be known as the "Age of Pericles." This period is regarded by most historians as one of the golden ages of Western society. Under the leadership of Pericles, Athens would go on to create a lasting legacy of great art, literature and philosophy.

IV. Democracy During the Age of Pericles

During the fifth century Athens initiated a great experiment in democracy that has yet to be duplicated. The democracy practiced in Athens at this time was direct rather than representative, which meant that every citizen had a voice in the Assembly (ekklesia). As citizenship was granted to all males over the age of 20 born of Athenian parents, this meant that a large number of Athenians (over 50,000) would have been able to vote in the Assembly. In practice, however, only a minority of citizens attended its meetings. The details of Athenian government were left to the Council of 500, a body of citizens chosen annually by lot. The top position in Athenian government was held by the 10 Generals, who were responsible for the defense of the city and who were elected annually by the Assembly.

This extraordinary form of government was undoubtedly as remarkable in its own time as it is in ours. As Pericles himself puts it:

"Our form of government does not enter into rivalry with the institutions of others. Our government does not copy our neighbors', but is an example to them. It is true that we are called a democracy, for the administration is in the hands of the many and not of the few. But while there exists equal justice to all and alike in their private disputes, the claim of excellence is also recognized; and when a citizen is in any way distinguished, he is preferred to the public service, not as a matter of privilege, but as the reward of merit. Neither is poverty an obstacle, but a man may benefit his country whatever the obscurity of his condition" (Funeral Oration).

As Pericles points out, even the very poor in Athens could become citizens and, therefore, had the right to sit in the Assembly. Athenian democracy also allowed for a high degree of freedom of speech, as is evidenced by the fact that Aristophanes could satirize elected officials during the height of the Peloponnesian War without incurring any penalties whatsoever (in fact, he won first prizes for his comedies).

It should be pointed out, however, that the benefits of Athenian democracy did not extend to all the members of the society. Women received little education, were considered the intellectual and physical inferiors of men, and had no political right. In effect they were little more than the property of their husbands. The complaint of women in Athenian society is echoed in Euripides' play, Medea:

Surely of all creatures that have life and will, we women

are the most wretched. When, for an extravagant sum,

We have bought a husband, we must then accept him as

Possessor of our body. This is to aggravate

Wrong with worse wrong. Then the great question: will the man

We get be bad or good? For women, divorce is not

Respectable; to repel the man, not possible. (Medea II 230-36)

The situation was even worse for slaves who made up almost half the population of Athens. Many of these slaves were captives, or the children of captives, taken during war or were purchased from non-Greek countries. Like women in Athens, slaves had no political rights.

V. The Achievements of the Greeks

It is not for nothing that Pericles called Athens the "School of Hellas." Prosperity, combined with a relatively unbroken period of peace led to Athens becoming the cultural envy of the Mediterranean world. Throughout the fifth century in Athens literature and the arts would blossom, "modern" history and science would come into their own, and the new discipline of philosophy would flourish as it would during no other period in human history.

Having defeated one of the greatest empires in the world at that time, the Athenians were filled with pride in their city, and that pride led to a heady sense of their own potential. Under the leadership of Pericles, the treasury of Delos was brought to Athens, and funds were siphoned off for the beautification of the city. While the ethics of this move may be questionable (the funds were supposed to be used for the joint defense of all the members of the Delian League), the results were that large sums were available for public works, such as the restoration of the Acropolis. The unparalleled freedom of speech and thought which was enjoyed by Athenians—a rarity in antiquity—also created an atmosphere of tolerance that fueled creative energy and inspired original thought.

The ascetic and intellectual ideal of the Athenians during the age of Pericles could be summed up as "[b]eauty with economy and without extravagance." (Sowerby 170). This principle applies as well to Greek literature and art as it does to the Greek approach to philosophy.

Art and Architecture

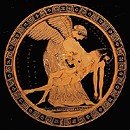

Art: The purpose of art in ancient Greece was for the honor of the gods and the state, not for the private pleasure of individuals. It was for this reason that art was displayed publicly and emphasized mythological subjects. Because Greek art served religious and civic purposes, it emphasized the dignity and nobility of its subjects.

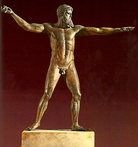

The first attempts to create life-sized statues out of stone in Greece occurred around 650 BC. Earlier attempts at sculpture had produced static statues with stiff postures similar to those found in Egypt at the time. During the fifth century, however, artists began to experiment with more natural poses. An interest in the human body also led to the creation of more naturally proportioned and anatomically detailed figures. There was also an attempt made during the fifth century to achieve an idealized image of man out of stone, using exact mathematical ratios. "The Greeks," Charles Crow observes, "saw the human form as the supreme embodiment of the ideal beauty, even their gods took the shapes of men. The Greek sculptor felt, therefore, that he must glorify the body, a temple of living splendor. Each classic statue represented all men, not a specific or individual man." (168-169). The figure of Poseidon below, with its outstretched arms, is a perfect illustration of this principle.

Pericles so dominated Athenian politics that the period in which he ruled has come to be known as the "Age of Pericles." This period is regarded by most historians as one of the golden ages of Western society. Under the leadership of Pericles, Athens would go on to create a lasting legacy of great art, literature and philosophy.

IV. Democracy During the Age of Pericles

During the fifth century Athens initiated a great experiment in democracy that has yet to be duplicated. The democracy practiced in Athens at this time was direct rather than representative, which meant that every citizen had a voice in the Assembly (ekklesia). As citizenship was granted to all males over the age of 20 born of Athenian parents, this meant that a large number of Athenians (over 50,000) would have been able to vote in the Assembly. In practice, however, only a minority of citizens attended its meetings. The details of Athenian government were left to the Council of 500, a body of citizens chosen annually by lot. The top position in Athenian government was held by the 10 Generals, who were responsible for the defense of the city and who were elected annually by the Assembly.

This extraordinary form of government was undoubtedly as remarkable in its own time as it is in ours. As Pericles himself puts it:

"Our form of government does not enter into rivalry with the institutions of others. Our government does not copy our neighbors', but is an example to them. It is true that we are called a democracy, for the administration is in the hands of the many and not of the few. But while there exists equal justice to all and alike in their private disputes, the claim of excellence is also recognized; and when a citizen is in any way distinguished, he is preferred to the public service, not as a matter of privilege, but as the reward of merit. Neither is poverty an obstacle, but a man may benefit his country whatever the obscurity of his condition" (Funeral Oration).

As Pericles points out, even the very poor in Athens could become citizens and, therefore, had the right to sit in the Assembly. Athenian democracy also allowed for a high degree of freedom of speech, as is evidenced by the fact that Aristophanes could satirize elected officials during the height of the Peloponnesian War without incurring any penalties whatsoever (in fact, he won first prizes for his comedies).

It should be pointed out, however, that the benefits of Athenian democracy did not extend to all the members of the society. Women received little education, were considered the intellectual and physical inferiors of men, and had no political right. In effect they were little more than the property of their husbands. The complaint of women in Athenian society is echoed in Euripides' play, Medea:

Surely of all creatures that have life and will, we women

are the most wretched. When, for an extravagant sum,

We have bought a husband, we must then accept him as

Possessor of our body. This is to aggravate

Wrong with worse wrong. Then the great question: will the man

We get be bad or good? For women, divorce is not

Respectable; to repel the man, not possible. (Medea II 230-36)

The situation was even worse for slaves who made up almost half the population of Athens. Many of these slaves were captives, or the children of captives, taken during war or were purchased from non-Greek countries. Like women in Athens, slaves had no political rights.

V. The Achievements of the Greeks

It is not for nothing that Pericles called Athens the "School of Hellas." Prosperity, combined with a relatively unbroken period of peace led to Athens becoming the cultural envy of the Mediterranean world. Throughout the fifth century in Athens literature and the arts would blossom, "modern" history and science would come into their own, and the new discipline of philosophy would flourish as it would during no other period in human history.

Having defeated one of the greatest empires in the world at that time, the Athenians were filled with pride in their city, and that pride led to a heady sense of their own potential. Under the leadership of Pericles, the treasury of Delos was brought to Athens, and funds were siphoned off for the beautification of the city. While the ethics of this move may be questionable (the funds were supposed to be used for the joint defense of all the members of the Delian League), the results were that large sums were available for public works, such as the restoration of the Acropolis. The unparalleled freedom of speech and thought which was enjoyed by Athenians—a rarity in antiquity—also created an atmosphere of tolerance that fueled creative energy and inspired original thought.

The ascetic and intellectual ideal of the Athenians during the age of Pericles could be summed up as "[b]eauty with economy and without extravagance." (Sowerby 170). This principle applies as well to Greek literature and art as it does to the Greek approach to philosophy.

Art and Architecture

Art: The purpose of art in ancient Greece was for the honor of the gods and the state, not for the private pleasure of individuals. It was for this reason that art was displayed publicly and emphasized mythological subjects. Because Greek art served religious and civic purposes, it emphasized the dignity and nobility of its subjects.

The first attempts to create life-sized statues out of stone in Greece occurred around 650 BC. Earlier attempts at sculpture had produced static statues with stiff postures similar to those found in Egypt at the time. During the fifth century, however, artists began to experiment with more natural poses. An interest in the human body also led to the creation of more naturally proportioned and anatomically detailed figures. There was also an attempt made during the fifth century to achieve an idealized image of man out of stone, using exact mathematical ratios. "The Greeks," Charles Crow observes, "saw the human form as the supreme embodiment of the ideal beauty, even their gods took the shapes of men. The Greek sculptor felt, therefore, that he must glorify the body, a temple of living splendor. Each classic statue represented all men, not a specific or individual man." (168-169). The figure of Poseidon below, with its outstretched arms, is a perfect illustration of this principle.

Architecture: As opposed to our own society, where people tend to spend lavishly on their own homes and ignore public buildings, in Athens the situation was exactly the opposite. Although most Athenians lived in rather poor homes, they were willing to invest large amounts of money on temples and other public buildings.

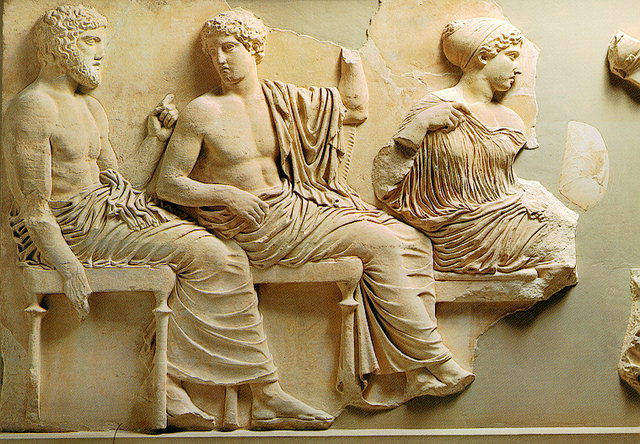

Among the most important buildings constructed during the fifth century is the Parthenon. Constructed on the Acropolis as a temple for the goddess Athena during the reign of Pericles, the Parthenon continues to awe visitors with its majestic splendor to this very day. The style of the Parthenon is basically quite simple: a raised rectangular box with doors surrounded by columns. The columns themselves are carved in the very simple Doric style (as opposed to the more ornate Ionian or Corinthian styles). The temple represents the best of Greek architectural style, emphasizing harmonious proportion and order. Although it is not evident today, the Parthenon, like all the temples of ancient Greece, was painted in bright colors, which must also have made it seem brilliant in the bright light.

Among the most important buildings constructed during the fifth century is the Parthenon. Constructed on the Acropolis as a temple for the goddess Athena during the reign of Pericles, the Parthenon continues to awe visitors with its majestic splendor to this very day. The style of the Parthenon is basically quite simple: a raised rectangular box with doors surrounded by columns. The columns themselves are carved in the very simple Doric style (as opposed to the more ornate Ionian or Corinthian styles). The temple represents the best of Greek architectural style, emphasizing harmonious proportion and order. Although it is not evident today, the Parthenon, like all the temples of ancient Greece, was painted in bright colors, which must also have made it seem brilliant in the bright light.

Literature, Drama and History

Literature: Upon reading a work of Greek poetry or drama, it will immediately become apparent that the style of these works often seems somewhat austere when compared to our own. Most Greek literature, notes Edith Hamilton, "is plain writing, direct, matter of fact. It often seems when translated with any degree of literalness, bare, so unlike what we are used to as even to repel." The aims of most Greek authors were clarity, simplicity and directness, an economy of expression, and a decided rejection of all embroidery (72-75). This love of the simple is evident in the following fragments from Greek poems:

"O evening star, that brings back all that bright dawn has scattered;

You bring the sheep, you bring the goat, you bring the child back to its mother."

"Take off your clothes and lie down.

We are not going to last forever."

Drama: It has been said that Western drama owes it beginnings to the Greeks. The first Greek drama was said to have been produced in Athens in 534 BC by Thespis (hence the origin of the word "thespian"), but it was in the fifth century that this art form reached its peak. Although there were over 4000 plays produced in Athens during Athen's "golden period," less than 50 of these have survived intact (Crow 140).

Dramas during this period were commissioned by the state and presented during one of the sixty religious festivals held each year. Among the most famous of these was the Festival of Dionysia, where each spring 15 plays were performed before an audience of almost 20,000 persons. These dramas were performed in open air theatres and typically lasted all day long. The purpose of Greek drama was not just entertainment, but was also ritualistic, because the festivals during which they were produced were held to honor the gods.

Greek drama differs from modern drama in many respects, not the least of which is the emphasis that it places on the heroic. Tragedy for a Greek always has to do with the sufferings of great individuals (i.e., Agamemnon, Oedipus), not that of ordinary men and women (i.e., Willie Loman or Blanche Du Bois). Greek drama also focuses on universal problems rather than contemporary ones. Finally, it uses material that would have been well familiar to an audience, typically borrowing events and characters from mythology or the Homeric legends.

Three of the most prominent dramatists during the fifth century were Aeschylus, Sophocles and Aristophanes. Aeschylus (525-456) wrote over 80 tragedies of which only seven survive. These works deal primarily with the heroes and gods portrayed in Homer's epics, and place a great emphasis on divine retribution for crimes and the suffering of the innocent. Aeschylus' major works include Agamemnon ad Electra. Sophocles (496-406) was said to have written 123 plays, but again, only seven of the these have been preserved for posterity. His works deal with the power of destiny in the lives of human beings, with the inevitable flaws (especially pride) of great individuals, and with the essentially tragic nature of the universe. In his most famous play, Oedipus the King, Oedipus, the hero, repeatedly tried to evade his fate, only to discover that he is the agent of his own demise. The theme of this work is clearly summed up by the chorus at the end of the play: "Sons and daughters of Thebes, behold: this was Oedipus,

Greatest of men; he held the key to the deepest mysteries;

Was envied by his fellow-men for his great prosperity.

Behold, what a full tide of misfortune swept over his head.

Then learn that mortal man must always look to his ending,

And none can be called happy until that day when he carries

His happiness down to the grave in peace." (1524-1530)

Finally, Aristophanes (448-385) primarily wrote comedies that mocked social conventions and parodied the leading politicians of his day. Among his most famous comedies are The Lysystrata and The Frogs.

History: The study of history in Greece really began in the 5th century with the writing of Herodotus and Thucydides. Herodotus (484-425), who is called the father of history, traveled extensively as a young man and acquired much factual knowledge about the lands and people he visited. His major work, the Histories (of the Persian Wars) demonstrates a flair for interesting stories and fascinating anecdotes. The scientific study of history begins with Thucydides (471-400), who improved on Herodotus by trying to be objective in his approach to history. Commenting on his own approach to history, Thucydides writes: "The absence of romance from my history will, I fear, detract somewhat from its interest; but if it be judged useful by those inquirers who desire an exact knowledge of the past as an aid to the interpretation of the future, which in the course of human things must resemble if it does not reflect it, I shall be content. In fine, I have written my work, not as an essay which is to win the applause of the moment, but as a possession for all time" (Peloponnesian War 1.22).

Philosophy: The terms "philosophy" for the ancient Greeks had a much broader connotation than it does for us today: the realm of philosophy applied to all those domains of reality to which rational thought was applied. Greek philosophy proper begins in the seventh century in Ionia with the philosopher Thales. Thales was one of the first thinkers that we know of to reflect rationally on what the primary substance of the universe was. His answer was water. Other thinkers would follow Thales creating their own hypotheses about the primal stuff out of which the universe was created, positing that it was air (Anaximenes), that it was perpetually in a state of flux (Heraclitus), that it was essentially unchanging (Parmenides), or that it was constituted of atoms (Democritus). These early Greek philosophers would lay the groundwork for the entire history of philosophy by presupposing that the universe was intelligible and that its nature could be discovered by using reason properly.

It was the fifth century (as well as the later fourth century), however, that saw some of the greatest achievements in philosophical thought. During this period, the Sophists were in Athens instructing young men in rhetoric (the art of persuading an audience). Their innovation was to espouse a kind of skepticism with respect to religious beliefs and philosophical knowledge and to embrace a relativistic approach to ethics. Their view of life is summed up by the sophist Protagoras, who claimed that "man is the measure of all things."

Literature: Upon reading a work of Greek poetry or drama, it will immediately become apparent that the style of these works often seems somewhat austere when compared to our own. Most Greek literature, notes Edith Hamilton, "is plain writing, direct, matter of fact. It often seems when translated with any degree of literalness, bare, so unlike what we are used to as even to repel." The aims of most Greek authors were clarity, simplicity and directness, an economy of expression, and a decided rejection of all embroidery (72-75). This love of the simple is evident in the following fragments from Greek poems:

"O evening star, that brings back all that bright dawn has scattered;

You bring the sheep, you bring the goat, you bring the child back to its mother."

"Take off your clothes and lie down.

We are not going to last forever."

Drama: It has been said that Western drama owes it beginnings to the Greeks. The first Greek drama was said to have been produced in Athens in 534 BC by Thespis (hence the origin of the word "thespian"), but it was in the fifth century that this art form reached its peak. Although there were over 4000 plays produced in Athens during Athen's "golden period," less than 50 of these have survived intact (Crow 140).

Dramas during this period were commissioned by the state and presented during one of the sixty religious festivals held each year. Among the most famous of these was the Festival of Dionysia, where each spring 15 plays were performed before an audience of almost 20,000 persons. These dramas were performed in open air theatres and typically lasted all day long. The purpose of Greek drama was not just entertainment, but was also ritualistic, because the festivals during which they were produced were held to honor the gods.

Greek drama differs from modern drama in many respects, not the least of which is the emphasis that it places on the heroic. Tragedy for a Greek always has to do with the sufferings of great individuals (i.e., Agamemnon, Oedipus), not that of ordinary men and women (i.e., Willie Loman or Blanche Du Bois). Greek drama also focuses on universal problems rather than contemporary ones. Finally, it uses material that would have been well familiar to an audience, typically borrowing events and characters from mythology or the Homeric legends.

Three of the most prominent dramatists during the fifth century were Aeschylus, Sophocles and Aristophanes. Aeschylus (525-456) wrote over 80 tragedies of which only seven survive. These works deal primarily with the heroes and gods portrayed in Homer's epics, and place a great emphasis on divine retribution for crimes and the suffering of the innocent. Aeschylus' major works include Agamemnon ad Electra. Sophocles (496-406) was said to have written 123 plays, but again, only seven of the these have been preserved for posterity. His works deal with the power of destiny in the lives of human beings, with the inevitable flaws (especially pride) of great individuals, and with the essentially tragic nature of the universe. In his most famous play, Oedipus the King, Oedipus, the hero, repeatedly tried to evade his fate, only to discover that he is the agent of his own demise. The theme of this work is clearly summed up by the chorus at the end of the play: "Sons and daughters of Thebes, behold: this was Oedipus,

Greatest of men; he held the key to the deepest mysteries;

Was envied by his fellow-men for his great prosperity.

Behold, what a full tide of misfortune swept over his head.

Then learn that mortal man must always look to his ending,

And none can be called happy until that day when he carries

His happiness down to the grave in peace." (1524-1530)

Finally, Aristophanes (448-385) primarily wrote comedies that mocked social conventions and parodied the leading politicians of his day. Among his most famous comedies are The Lysystrata and The Frogs.

History: The study of history in Greece really began in the 5th century with the writing of Herodotus and Thucydides. Herodotus (484-425), who is called the father of history, traveled extensively as a young man and acquired much factual knowledge about the lands and people he visited. His major work, the Histories (of the Persian Wars) demonstrates a flair for interesting stories and fascinating anecdotes. The scientific study of history begins with Thucydides (471-400), who improved on Herodotus by trying to be objective in his approach to history. Commenting on his own approach to history, Thucydides writes: "The absence of romance from my history will, I fear, detract somewhat from its interest; but if it be judged useful by those inquirers who desire an exact knowledge of the past as an aid to the interpretation of the future, which in the course of human things must resemble if it does not reflect it, I shall be content. In fine, I have written my work, not as an essay which is to win the applause of the moment, but as a possession for all time" (Peloponnesian War 1.22).

Philosophy: The terms "philosophy" for the ancient Greeks had a much broader connotation than it does for us today: the realm of philosophy applied to all those domains of reality to which rational thought was applied. Greek philosophy proper begins in the seventh century in Ionia with the philosopher Thales. Thales was one of the first thinkers that we know of to reflect rationally on what the primary substance of the universe was. His answer was water. Other thinkers would follow Thales creating their own hypotheses about the primal stuff out of which the universe was created, positing that it was air (Anaximenes), that it was perpetually in a state of flux (Heraclitus), that it was essentially unchanging (Parmenides), or that it was constituted of atoms (Democritus). These early Greek philosophers would lay the groundwork for the entire history of philosophy by presupposing that the universe was intelligible and that its nature could be discovered by using reason properly.

It was the fifth century (as well as the later fourth century), however, that saw some of the greatest achievements in philosophical thought. During this period, the Sophists were in Athens instructing young men in rhetoric (the art of persuading an audience). Their innovation was to espouse a kind of skepticism with respect to religious beliefs and philosophical knowledge and to embrace a relativistic approach to ethics. Their view of life is summed up by the sophist Protagoras, who claimed that "man is the measure of all things."

Perhaps the greatest philosopher of all is Socrates (469-399 BC). Socrates has been called the "father of philosophy" even though he never wrote a word or developed any system of thought himself. His lasting legacy to philosophy was to develop what has come to be known as the "Socratic method," an approach that uses questions and answers to refute the groundless opinions of others and to lay the foundation for true knowledge. In 399 B.C. Socrates was put on trial for atheism and for corrupting the youth of Athens. His defense speech to the Athenian jury that tried him has been recorded in Plato's Apology.

Socrates' disciple, Plato (428-347), was present during his master's trial in 399. After Socrates was put to death, Plato forsook the political career that he was planning and dedicated himself to philosophy. Besides being the author of 42 philosophical dialogues, Plato also founded the Academy, which was one of the great philosophical schools of the ancient world. The most prominent of Plato's pupils was the philosopher Aristotle, who would eventually go on to found his own school, the Lyceum.

Socrates' disciple, Plato (428-347), was present during his master's trial in 399. After Socrates was put to death, Plato forsook the political career that he was planning and dedicated himself to philosophy. Besides being the author of 42 philosophical dialogues, Plato also founded the Academy, which was one of the great philosophical schools of the ancient world. The most prominent of Plato's pupils was the philosopher Aristotle, who would eventually go on to found his own school, the Lyceum.

VI. The Decline of Athens

Unfortunately all great civilizations must eventually pass away, and this was true for Athens as well. 431 saw the start of the Peloponnesian War, which would last on and off for 27 years. The war was fueled by Athens' rapid expansion and the jealously that it created among other Greek city-states, most notably, Sparta and Corinth. At the beginning of the war those living in rural parts of Attica took refuge behind the walls of Athens. Lack of proper sanitation led to the outbreak of plague in 431-429. This caused the deaths of hundreds in Athens, including Pericles and his sons.

An absence of strong leadership, combined with the effects of the plague, eventually led to Athens' defeat by Sparta in 404. The terms of the peace settlement required that Athens tear down the walls of its city, to reduce its navy and to submit itself to the leadership of Sparta. The Spartan leader, Lysander, also imposed an oligarchical form of government on Athens in which 30 individuals exercised complete rule over the city. This new form of government, however, proved unworkable and democracy was restored in Athens in 402 BC. It was this restored democratic government that would eventually put Socrates to death in 399 for his decidedly undemocratic views.

Weakened by constant warfare, the Greek city-states were ripe to be conquered by a foreign power, and Philip, the king of Macedonia, was determined to expand his state. After conquering Thessaly and Thrace, he turned his attention to Greece. Under the inspiration of Demosthenes, Athens led a federation against Philip, but were badly defeated at Chaeronea (388 BC). Philip compelled the conquered Greek city states to join a Hellenic League that bound them closely to him. Upon the murder of Philip, the throne and armies of Macedonia passed to his twenty year old son, Alexander. Alexander was the pupil of the philosopher Aristotle, and had ambitions to hellenize the entire world. By 331 he succeeded in conquering Persia, Syria and Palestine, Egypt and part of India before he died at the age of 33.

Unfortunately all great civilizations must eventually pass away, and this was true for Athens as well. 431 saw the start of the Peloponnesian War, which would last on and off for 27 years. The war was fueled by Athens' rapid expansion and the jealously that it created among other Greek city-states, most notably, Sparta and Corinth. At the beginning of the war those living in rural parts of Attica took refuge behind the walls of Athens. Lack of proper sanitation led to the outbreak of plague in 431-429. This caused the deaths of hundreds in Athens, including Pericles and his sons.

An absence of strong leadership, combined with the effects of the plague, eventually led to Athens' defeat by Sparta in 404. The terms of the peace settlement required that Athens tear down the walls of its city, to reduce its navy and to submit itself to the leadership of Sparta. The Spartan leader, Lysander, also imposed an oligarchical form of government on Athens in which 30 individuals exercised complete rule over the city. This new form of government, however, proved unworkable and democracy was restored in Athens in 402 BC. It was this restored democratic government that would eventually put Socrates to death in 399 for his decidedly undemocratic views.

Weakened by constant warfare, the Greek city-states were ripe to be conquered by a foreign power, and Philip, the king of Macedonia, was determined to expand his state. After conquering Thessaly and Thrace, he turned his attention to Greece. Under the inspiration of Demosthenes, Athens led a federation against Philip, but were badly defeated at Chaeronea (388 BC). Philip compelled the conquered Greek city states to join a Hellenic League that bound them closely to him. Upon the murder of Philip, the throne and armies of Macedonia passed to his twenty year old son, Alexander. Alexander was the pupil of the philosopher Aristotle, and had ambitions to hellenize the entire world. By 331 he succeeded in conquering Persia, Syria and Palestine, Egypt and part of India before he died at the age of 33.

VII. Suggestions for Further Reading

- Crow, Charles. Greece: The Magic Spring. New York: Harper and Row, 1970.

- Freeman, Charles. The Greek Achievement. New York: Viking, 1999.

- Grant, Michael. The Founders of the Western World: A History of Greece and Rome. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1991.

- Hamilton, Edith. The Greek Way. New York: W.W. Norton, 1942.

- Hardy, W.G. The Greek and Roman World. Cambridge, MA: Schenkman, 1962.

- Martin, Thomas R. Ancient Greece: From Prehistoric to Hellenistic Times. New Haven: Yale UP, 1996.

- Sowerby, Robin. The Greeks: An Introduction to Their Culture. London: Routledge, 1995.

© Michael S. Russo, 2001. This text is copyright. Permission is granted to print out copies for educational purposes and for personal use only. No permission is granted for commercial use.